Tropicália: The Most Important Musical Movement You’ve Never Heard Of

Learn Portuguese While Discovering Tropicália — Brazil’s Legendary Musical Revolution

Portuguese is the fifth most spoken language in the world, with almost 200 million native speakers in Brazil alone. It’s spoken in over 10 other countries across 4 continents.

There are a ton benefits from learning Portuguese: it could improve your job prospects in an increasingly globalized world, it could enrich your travel experiences… or it might simply allow you to watch your favorite Brazilian Netflix shows and not miss anything in translation!

But, in addition to all that, learning Portuguese can also give you the opportunity to connect with a number of cultures all over the world in a much richer and more authentic way. And, the converse is true, too: experiencing the cultures of Portuguese-speaking people can give you a unique insight into the language.

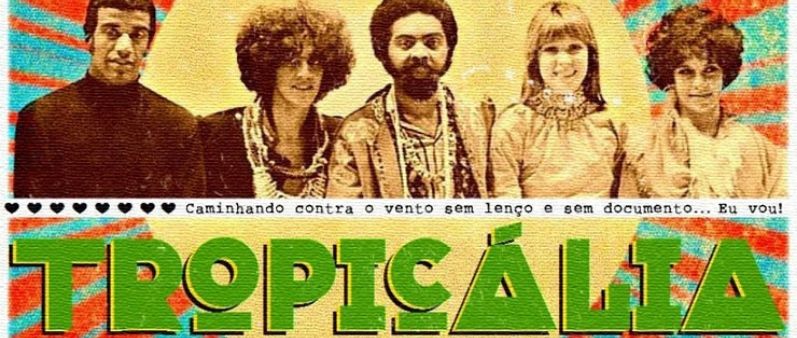

In this article, I want to introduce you to one of the most important cultural revolutions that you probably haven’t heard of: Tropicália or “Tropicalism”. Knowing a little about the Tropicalist movement can bring you closer to Brazilian Portuguese and give you a better understanding of Brazilian culture.

What is the Tropicália Movement?

Tropicália hasn’t made it to many museums, but it was a revolution so strong that Brazilian music—and politics—would never be the same after.

You may never have heard that name before, but you might have come across some of the art that came out of the Tropicalism movement, or some of the music influenced by it. Tropicalism has been cited as an influence by rock musicians such as David Byrne, Beck, The Bird and the Bee, Arto Lindsay, Devendra Banhart, El Guincho, Of Montreal, and Nelly Furtado.

How Did Tropicália Begin?

Tropicália began in the late 1960s. The entire Western world was going through cultural change. The U.S. was engaged in a war in Vietnam, while young people were flocking to the hippie movement and endorsing peace and love.

In South America, Brazilian popular culture was going through a more drastic upheaval, as the country’s democratically elected president was overtaken by the military. Soon after taking control, the military dictatorship censored and froze certain kinds of artistic production, especially those it saw as critical of the regime.

At the same time as this important political change, Rock music began to enter Brazil from North America. Many Brazilian artists were concerned about the arrival of Rock in Brazil, seeing it as an invasion of foreign music and a threat to Brazilian culture. These people were also critical of the role of the US government in supporting the dictatorship. Some artists even protested in a march against the electric guitar—what they saw as a symbol of American imperialism.

It was during that time that one of Brazil’s most famous singers, Caetano Veloso, performed at the Festival Record de Música Popular Brasileira (the “Popular Music of Brazil Record Festival”)—with the song Alegria, Alegria (“Joy, Joy”), which mixed Brazilian rhythms with electric guitar rock.

Caetano Veloso

The performance shocked the audience, as Veloso intended. Gilberto Gil, another of Brazil’s most famous musicians, supported Veloso with a rock version of his song Domingo no Parque (“Sunday in the Park”). These performances marked the beginning of Tropicália—a kind of fusion of the rebellious rock’n’roll from the United States with the native rhythms of Brazil’s traditional music.

Tropicália Sought to Unify Brazilian Culture

Tropicália was initiated by Caetano Veloso and also elaborated by him. The lyrics to his song Tropicália describe this melding of the people and cultures into one Brazilian, multicultural identity. The song demonstrates this, blending the influence of African rhythms, with American and English guitars and drumming in a pop-rock style. Ultimately Caetano and his collaborators created a “manifesto” for the movement in the form of an album: Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis.

Tropicalism redefined Brazilian music—which, until 1967, seemed to have had its peak with Bossa Nova, a mix of jazz and samba. With a completely new style, Tropicalists like Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil mixed psychedelia with Maracatu, samba, pop, and Capoeira. In doing this, they saw themselves as confronting the elitist musical genres and the more conservative roots of Bossa Nova.

Tropicalism became more than simply a musical revolution, but an aesthetic one. With necklaces, dresses, and makeup—symbols that flew in the face of the norms of the time about masculinity and morality—Tropicalist artists like Caetano Veloso had very rich visual references.

Arnaldo Baptista, from the rock group Os Mutantes, wore Romeo and Juliet-style clothes with a traditional northeastern Brazilian hat and a haircut that imitated the Beatles. His bandmate, Rita Lee, dressed in colorful clothes, witch hats, wedding dresses, and symbols of the American flower power movement. Their visual influences ranged from Brazilian icon Carmen Miranda to Andy Warhol’s pop art, always aiming to be exaggerated, colorful, flashy, and strong—like Brazilian culture.

A Critique of Brazilian Mainstream Culture—and Politics

The Tropicalist movement caused transformations not only in music, but also in film, theatre, and poetry. The movement aimed to challenge the restrictive and conservative traditions of the past and challenged popular norms of morality and behavior. Through it, the hippie counterculture was brought into Brazil, including the symbols of peace, the fashions of long curly hair, and brightly colored clothes.

More than simply a cultural criticism, it was a political one. One song of Veloso’s, É Proibido Proibir (“It’s Forbidden to Forbid”) was a very direct criticism of the dictatorship’s censorship. The Tropicalist performances and shows fed a fire of resistance against the military dictatorship. In response, the government responded by trying to censor the Tropicalists.

At the end of 1968, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were awoken by police and taken to prison. They were arrested without charge, held in solitary confinement for months, and finally exiled to England until the early 1970s when they were allowed to return to Brazil.

Tropicalism became a cry for freedom in the midst of a repressive culture and the most tyrannical regime in Brazil’s history. But this cry lasted only a year before it was being repressed by the military dictatorship. Still, it’s short life had long-lasting effects: it started the embers of the counterculture that would eventually end the dictatorship and changed Brazilian music forever.

The 5 Best Artists and Albums to Discover Tropicália

Interested in discovering the music at the center of this cultural and political revolution? I’ve collected some of the classics here; just choose an artist, start listening, and learn a little more Portuguese. Here are five of the best artists and albums to discover Tropicália.

1. Various Artists: Tropicalia ou Panis et Circensis [1968]

The album represents the apex of the Tropicalist movement and gathers the greatest names of Tropicalism: Caetano Veloso, Gal Costa, Gilberto Gil, Nara Leão, Os Mutantes and Tom Zé. Listen to Panis et Circensis (by Os Mutantes) as a good starting point.

2. Os Mutantes: Os Mutantes [1968]

Try the classic Baby for a taste of Os Mutantes (“The Mutants”).

3. Tom Zé – A Grande Liquidação (1968)

One of the most popular tracks from this album by Tom Zé is São São Paulo and is a great place to start.

4. Gal Costa: Gal Costa (1969)

Check out especially Baby on this classic album by Gal Costa.

5. Novos Baianos: Acabou Chorare (1972)

The Novos Baianos were among the most famous bands in Brazil. Check out their track Mistério do Planeta (Novos Baianos) for some of their work that comes directly from the Tropicália movement.

Understanding Brazilian Culture Will Help You Learn Portuguese

Brazil is more than soccer, the rainforest, and Carnival. The culture of this country that is the size of a continent is a rich fusion of European, Asian, and African cultures together with the various indigenous communities. Brazil has created something unique from bringing all these influences together. Tropicalia was powerful in that it did that in a new way; it merged popular American rock music with its own language and sounds to create something completely new.

Language and culture are interconnected; understanding one helps you understand the other. The Tropicália movement had a massive effect not just on the art of the 1960s, and not just on politics, but on how Brazilians saw themselves.

If you are learning Portuguese and want to learn more about this period of Brazilian history, check out this documentary. You can activate Portuguese subtitles to further improve your learning, or, if you prefer, you can activate machine translation in English.

If you haven’t already, get your free lesson from Pimsleur to start learning Portuguese. The Pimsleur method is one of the most effective ways to learn a language. But also, don’t forget that learning a language can be much easier and more fun when you build in some real contact with culture! The music of Tropicália might be just the thing to get you motivated to properly learn Brazilian Portuguese.

Thinking about learning Portuguese? Try a FREE LESSON on Pimsleur.