Ningún vs. Ninguno: Ultimate Guide to Mastering Spanish Short Form Words

Ningún vs. Ninguno, Tan vs. Tanto, Algún vs. Alguno: The Ultimate Breakdown of Spanish Apocopation

Ever wondered when to use ningún vs. ninguno, tan vs. tanto, or algún vs. alguno?

Apocopation is not, in fact, a typo for “apocalypse” (although both words share the same origins and can seem equally daunting).

From the Ancient Greek apó meaning “from, away from” and kóptō meaning “to cut”, apocopation is the technical term for a word formed by removing the end of a longer word.

Say what now?

In English, we know apocopated words mostly as nouns: gymnasium → gym, abdominals → abs.

This is important because the Spanish language also has many of these short-form words that are used in daily conversation, and these can be particularly difficult for Spanish learners to get the hang of.

That’s why we’ve compiled a list of the most common Spanish shortened adjectives, pronouns, and adverbs, so you can navigate these bad boys with ease!

We’ll go over:

- Apocope Definition

- When to Shorten Spanish Words

- Spanish Apocope Examples

Apocope Definition

The most basic definition of apocopation is the shortening of words or omitting the last letter, syllable, or part of a word.

Words like “admin” instead of administration, “fab” instead of fabulous, or “totes” instead of totally, for example. There are various reasons this occurs. Sometimes it’s for slang, sometimes for grammar.

When Should I Shorten Spanish Words?

Some Spanish adjectives are shortened when they come before a noun. For example, the adjective ninguno/a (no/none), when used before a masculine noun, turns into ningún.

The apocope depends on the gender and plurality of a given word. If the noun is plural and/or feminine, then the apocopation doesn’t happen i.e. ninguna mujer (no woman) or ninguno de ellos (none of them). The subject must be singular and masculine for the word to be shortened i.e. ningún hombre (no man).

Top 14 Shortened Spanish Words (a.k.a. Spanish Apocopes)

Here is a list of the most important Spanish short form adjectives, pronouns, and adverbs that are used every day, accompanied by example sentences.

1. Ninguno vs. Ningún

Ninguno is what is called a negative adjective, meaning no or none. It follows the pattern ninguno + de + noun. See how it compares to its apocopate version ningún below.

Ninguno de ellos querían ir a la playa. “None of them wanted to go to the beach.”

Ningún niño quería ir a la playa. “No boy wanted to go to the beach.”

In the first sentence, the subject ellos (them) is plural and masculine. Because the subject is plural, ninguno was not shortened to ningún.

*Notice that the word ninguno is not plural even though the subject is. That is because ninguno is only used in negative sentences to mean “none”, and you simply cannot have plural nothingness.

In the second example sentence, the subject is niño, which is singular and masculine. This resulted in the -o being removed.

2. Alguno vs. Algún

Alguno (some) is an adjective that follows the pattern algunos + de + noun, whereas algún directly precedes a noun.

Algunos de los carros están rotos. “Some of the cars are broken.”

Algún día quiero ser un abogado. “Someday I want to be a lawyer.”

In the first example, the subject los carros (the cars) is plural and masculine. Because of the plurality, algunos was not shortened to algún. Notice that algunos is plural, because “some” can indicate a quantity above one.

In the second example sentence, the noun día is singular and masculine, which resulted in the “o” being removed.

3. Cualquiera vs. Cualquier

Cualquiera is a pronoun that can mean any, either, or whichever. Una cualquiera, in its colloquial form, refers to a person of no meaning, someone who could be replaced by anyone.

Cualquiera on its own always ends in “a” (cualquiero does not exist) and will follow the pattern cualquiera + de + noun.

When the apocope cualquier is used, it always precedes a noun and thus loses the a, following the pattern cualquier + noun.

Con cualquiera de los dos vestidos luces delgada. “You look thin with either of the two dresses.”

Cualquier vestido te va a lucir bien. “Either dress will look good on you.”

Like any mystery, there must be an explanation.

4. Uno vs. Un

Remember the simpler days of the game Uno?! You would shout “Uno!” when you only had one card left in your hand. Years later when you started Spanish 1, you probably learned the word un gato (a cat) and you wondered what happened to the word uno!

That’s because un is apocopate form of uno!

Uno refers to the number one when used by itself or the pronoun, i.e. Antonio es uno de los hombres más brutos que yo he conocido (one of the stupidest men I’ve ever met).

On the other hand, un is used as an article for a singular masculine noun, i.e. un hombre (a man).

See another example below.

(Pronoun) Quiero leer uno de los libros. “I want to read one of the books.”

(Article) Quiero leer un libro. “I want to read a book.”

5. Primero vs. Primer

Which comes first?! Primero (first) is an ordinal number, i.e. primero, segundo, tercero (first, second, third). Primero is used instead of its apocopate form primer when using it as an ordinal number.

Primero, tengo que ir a europa. “First, I need to go to Europe.”

Use primer when using it to describe a singular, masculine noun.

El primer país que voy a visitar es España. “The first country I am going to visit is Spain.”

6. Tercero vs. Tercer

Tercero (third) is also an ordinal number in the first, second, third sequence, whereas tercer is used as an adjective in front of a singular, masculine noun (rules for primero/primer above).

Tercero, quiero subir a la Torre Eiffel. “Third, I want to go up the Eiffel Tower.”

El es el tercer hombre en la fila. He is the third man in line.

7. Postrero vs. Postrer

Postrero is from the same root as the English word posterior, meaning last, usually in a series. It follows the same rules as primero/primer and tercero/tercer.

El anotó un punto en los postreros momentos del juego. “He scored a point in the last moments of the game.”

El 31 de diciembre es el postrer día del año. “December 31st is the last day of the year.”

Note that in the first example, the word postrero is used in its plural form, postreros momentos (last moments).

8. Ciento vs. Cien

Buckle your seatbelts for this bumpy grammar ride!

Ciento (one hundred) used on its own is a cardinal noun, representing the number 100 itself. Ciento is also used for percentages (notice the cent in percent, from Latin centum 100.)

Examples of ciento:

Ciento diez. “One hundred and ten.”

Hubo un aumento de veinte por ciento en las ventas. “There was a twenty percent increase in sales.”

Cien is an apocopate form of the word ciento and is used in front of nouns, regardless of gender.

He comprado cien libros (m). “I’ve bought one hundred books.”

He contado cien personas (f). “I’ve counted one hundred people.”

The apocope also precedes mil, millón, and billón (a thousand, a million, and a billion), because they are masculine nouns.

- Cien mil. (One hundred thousand.)

- Cien millón. (One hundred million.)

- Cien billón. (One hundred billion.)

BUT (and you know there was a but coming) when used as a pronoun, as in “hundreds of people”, you would use ciento de instead of cien. See the example below.

Hay cien personas en el auditorio. “There are one hundred people in the auditorium.”

Hay cientos de personas en el auditorio. “There are hundreds of people in the auditorium.”

Just remember that cien does NOT have a plural (cienes does not exist). Therefore, when it is plural, use cientos.

9. Malo vs. Mal

Malo (bad) is a masculine adjective that always follows the noun, i.e. un chico malo (a bad boy). Alternatively, it can be used without a noun at all, as in an exclamation of malice, i.e. ¡Qué malo! (How bad!).

Juan es malo. “Juan is bad.”

Mal is the apocopate form of malo, also an adjective, that comes before a given masculine noun.

Juan es un mal amigo. “Juan is a bad friend.”

Mal can also be an adverb, in which case it translates to poorly, as in me siento mal (I’m feeling bad).

Estoy mal acostumbrada. “I’m poorly accustomed.”

No me gusta Juan – me cae muy mal. “I don’t like Juan. He rubs me the wrong way.”

10. Bueno vs. Buen

Both bueno and buen (good) follow the same rules as malo/mal above.

El ejercicio es bueno para tu salud. “Exercise is good for your health.”

¡Qué bueno! “How good/lovely!”

¡Qué tengas un buen día! “Have a good day!”

11. Santo vs. San

Sound holy? Both Santo and San mean saint but they follow different grammatical rules. Santo is used when talking about saints in the general sense without specific names.

Espero que los santos me bendigan hoy. “I hope the saints bless me today.”

Santo is also used for specific saint names that start with Do- or To-.

For instance:

Santo Domingo or Santo Tomás.

For other saint names, the apocopate san is used. You might recognize many cities in California and all over Latin America that follow this pattern.

San Diego, San Martin, San Juan, San Jose, etc.

12. Tanto vs. Tan

Tanto and tan are more like fraternal twins of the apocopates. Tanto/a is an adjective meaning so much or so many, while tan is an adverb used with adjectives that can mean so, much, or as.

You should use tanto/a to describe in number a noun, or the sentence structure tanto + como to as “as much as” or tanto/as + noun + como to say “as many ___ as”.

Hay tanta gente en esta fiesta. “There are so many people in this party.”

Nadie llora tanto como ella! “No one cries as much as she does.”

No conozco tantas personas como Roy! “I haven’t met as many people as Roy has.”

Ay love, it hurts me so!

Tan is used to modify an adjective or adverb, and follows the pattern tan + adjective to describe “so ___” or tan + adjective + verb to describe “as ___ as…”

Los mangos están tan deliciosos que me los comí todos. “The mangoes are so delicious that I ate them all.”

Los elefantes corren tan rápido como las jirafas. “Elephants run as fast as giraffes.”

13. Cuánto vs. Cuán

Cuánto can mean how much, the more, and a lot. Similar to other words on this list, cuánto normally proceeds nouns and verbs. Both cuánto and cuán are used in questions and exclamations.

¿Cuánto cuesta? “How much does it cost?”

¿Cuántas personas van? “How many people are going?”

Cuán more closely translates to “so” or “how” in English. It is used with adverbs and adjectives, following the sequence cuán + adjective or cuán + adjective + verb.

Here are some examples of cuán in a sentence:

(Question) ¿Cuán difícil es tu problema? “How difficult is your problem?”

(Exclamation) ¡Cuán grande es tu amor ! “How great is his love!”

However, the reality is that this apocope is quite formal for spoken Spanish. Usually, you can replace the use of cuán with inquiries using question words like qué or cómo. It is mostly used in poetry and literature, i.e. the song “Cuán Grande Es Tu Amor”.

To see how obsolete the word cuán has become in everyday life, just take a look at this simple example of a Google search with the question word “¿Cuán?” below.

When you search ¿Cuán rápido crece el pelo? (how fast does hair grow?), you see that the related articles that pop up give the same inquiry with different question words:

- ¿Cuánto tarda en crecer el pelo? (How long does it take for hair to grow?)

- ¿Qué tan rápido puede crecer el cabello? (How fast can hair grow?)

- ¿A qué velocidad crece el pelo? (At what speed does hair grow?)

14. Grande vs. Gran

Grande, which means big in size, is an adjective that appears after a noun.

El perro es grande. “The dog is big.”

It’s apocopated version gran is also an adjective used to emphasize how great/amazing/big a given noun is, but it always precedes the noun. Additionally, the noun can be either masculine or feminine.

Es una gran idea. “It is a good idea.”

Ese perro es un gran problema. “That dog is a big problem.”

Finally Figured Out Ningún vs. Ninguno? Continue to Strengthen Your Spanish!

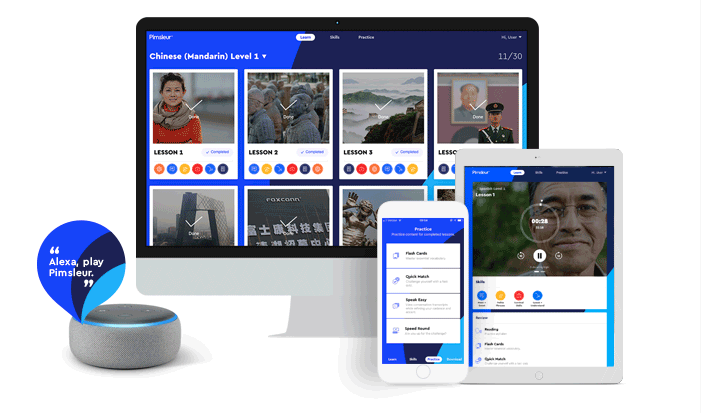

Now that you’ve learned about shortening your adjectives, it’s time to shorten your language learning struggles. Check out Pimsleur today for a free Spanish lesson and choose to learn Castilian Spanish or Latin American Spanish.