Use and Abuse of the Word Literally – A Crisis of Language?

How the Term ‘Literally’ has Changed Over Time

“That chili was so hot it literally blew my head off”

“She literally flew off the handle”

“That person literally makes my blood boil”

Literally.

It’s the infamous term that infuriates editors, academics, linguists, publishers, and journalists alike, with people using it when they actually mean ‘figuratively’ – the exact opposite.

Encouraged by widespread use in celebrity and pop culture, this innocent(ish) adverb exploded into a senseless filler word around 20-30 years ago and is now used liberally and without question by the young (and old, but especially the young), to give their sentences extra ‘oomph’. The problem is that the word has a specific and useful meaning, which is being diluted and devalued by its overuse in incorrect contexts.

It is truly a crisis of language.

At least, that’s what you’d think had happened by some of the reactions to the word ‘literally’. There seems to be a ‘literal panic’ these days around the use of the word ‘literally’’. Linguistic prescriptivists – who generally prefer to keep the existing rules of English – have penned dozens of commentaries and articles on the subject to illustrate their rage.

The reality is, in fact, much less extreme.

Let’s (figuratively) dive into the history of the word ‘literally’.

‘Literally’ – Language Evolution or Butchery? When did the Literal Panic Start?

The phenomenon of overusing ‘literally’ feels like an issue from the 21st century, but the reality is that this is not the case. ‘Literally’ is nothing new, unusual or harmful, and the current panic about the loss of original meaning is somewhat misplaced.

Non-literal ‘literally’ has been used for centuries!

What’s more, not only is it not a new thing, but the current controversial meaning – hyperbole and emphasis – developed gradually and legitimately over time through genuine linguistic change processes.

The History of the Term Literally

‘Literally’ has origins in borrowings from French and Latin. The French word literal means ‘relating to letters or literature’, and the Latin word litteralis describes ‘taking words in their natural or customary meaning, without any ulterior spiritual or symbolic meaning’.

The first borrowings of these words can be dated back to the early 1400s. In around 1450, the first example of the words literal and literally as we know them today (i.e. a word describing the primary sense of a concept) appeared.

By 1670, another meaning for the word literally had surfaced. OED described this as “to indicate that the related phrase or word must be taken in its literal sense, usually to add emphasis.”

An example of this:

“What punishment has he suffered? Literally none.”

This new meaning of literally, designed to add emphasis, served as the precursor to today’s controversial, hyperbolic usage.

The process of the word gaining this new meaning took place through a steady language change process: bridging contexts.

Literal Change: Words Gaining Extra Meanings Through Bridging Contexts

While it may seem illogical for a word to evolve from having one exact meaning to then acquiring a second, opposite meaning, it is an interesting process that took literally to also mean ‘figuratively’.

In the example above, where literally was added to the word none to illustrate the lack of punishment, there are two possible interpretations for the word literally: the original (‘taken in a literal sense’) and the new meaning, where literally adds emphasis.

Either interpretation would make sense in its own right, and in fact, it’s even possible for the word literally to serve both purposes – descriptive and emphatic – in this context. We have no way of knowing in which sense the writer chose the word literally.

What is a Bridging Context?

The ambiguity behind this example makes it a bridging context, or a term used in a way that signals multiple possible interpretations. Readers interpreted the word in both original and emphatic senses, ultimately validating the emphatic literally.

With continuous use of literally in this ambiguous way, the meaning of the word gradually shifted further, culminating in the following excerpt from a 1769 text:

“He is a fortunate man to be introduced to such a party of fine women at his arrival; it is literally to feed among the lilies”

In this sentence, there is no other possible definition of literally except the hyperbolic.

While it is related to the emphatic literally, it bears no resemblance to the original definition, ‘taken in a literal sense’.

This shows the full cycle of bridging contexts, with literally on the ‘other side of the bridge’ in this example, so to speak.

How Often Does Language Change Happen?

Language change is a continuous and gradual process.

New words, phrases, and structures become trendy among language speakers, leading to increased popularity, widespread use, and then standardization through inclusion in the dictionary.

This change, and the inclusion of new terms in the dictionary, is nothing to be afraid of; it’s been happening since the beginning of time.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw countless language changes: the Internet, computers, and globalization have all provided catalysts for new word meanings.

The word spam is a perfect example of language change: originally a portmanteau of ‘spiced ham’ to describe a British processed meat product, its primary meaning now describes unwanted digital communications.

So Why do We See Literally as so Negative?

Now we understand where the modern literally came from, is it still correct that it receives such bad press?

Although it is now regarded as a contronym (a word with two opposite meanings), there are hundreds of other contronyms in the English language, which are nowhere near as controversial (custom, dust, model, etc).

Language prescriptivists (people who disapprove of semantic change) have the loudest voices when it comes to criticizing literally, but in reality, the figurative definition of the word has been listed in the OED since 1903.

Stanford linguist Arnold Zwicky suggests that we criticize the word literally so harshly because of the recency illusion: a phenomenon where we believe that something is recent because we ourselves only recently discovered it. When we know that ‘literally’ annoys us, we’re more likely to notice it.

This is related to confirmation bias, and for those who are irked by literally’s explosion in popularity, it will be easy to find endless examples of its (mis)use to support their anger.

Language change is inevitable. New words and meanings evolve while old ones fall into obscurity and obsolescence. There is always a resistance to change from prescriptivists, but the vendetta against literally is unusual because it is not a new phenomenon.

At some point in the early 20th century, the alternative definition for literally was no longer a misuse, but finally achieved the status of a new definition.

What is more, although it annoys some people, everyone understands the hyperbolic meaning of literally. If the purpose of language is to be able to communicate, then surely the new meaning fulfills the purpose perfectly?

Language is constantly evolving, and it is exactly this element of change that makes it so interesting.

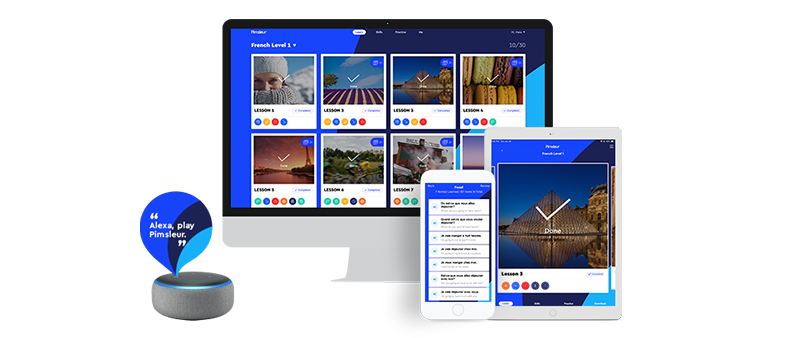

Pimsleur Language Learning Will Literally Blow Your Mind!

You might think learning a new language may seem like a huge challenge. But you can start speaking a new language in just a few days. With Pimsleur Language Programs, you’ll learn a language by speaking it, not by studying it. You’ll be speaking the language on Day 1. After 30 days, you will be speaking with a near-native accent!

Try our app today. Your first language lesson is on us.